01. November 2021

Close up

“Tomorrow becomes today and today becomes yesterday.”

by Sabine Apostolo

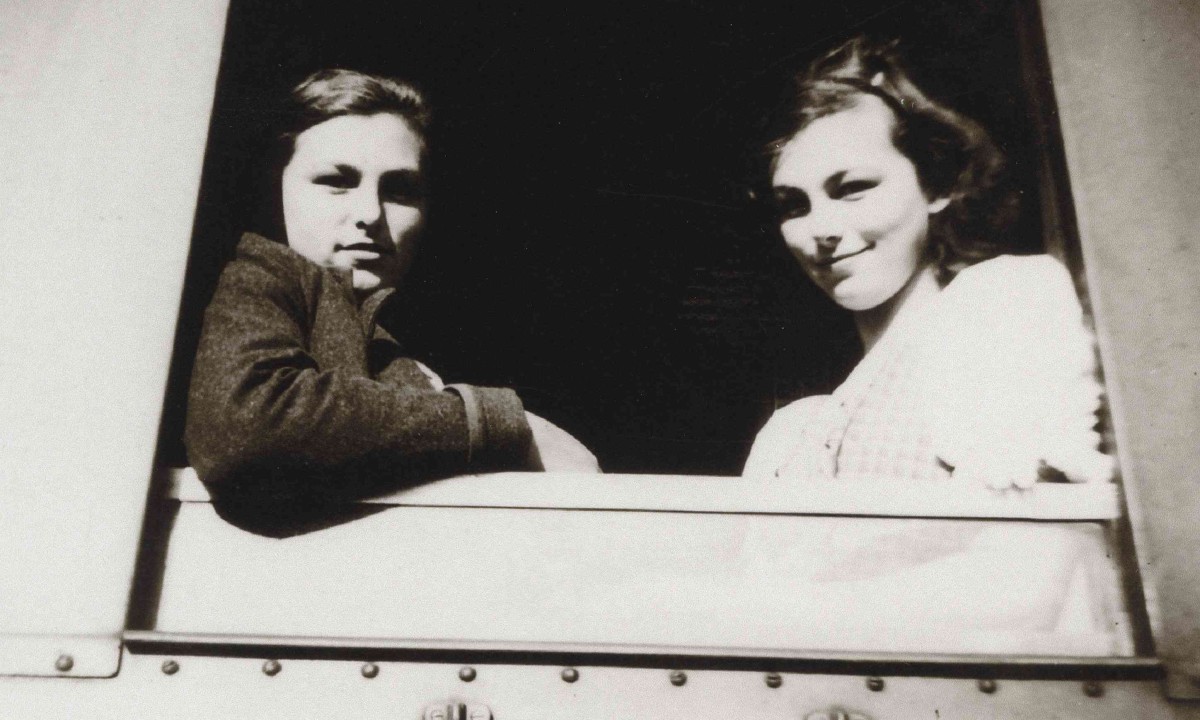

One hundred years ago, on November 1, 1921, the twins Helga and Ilse Aichinger were born in Vienna. Seventeen years later, they had to separate because they had at least “two wrong grandparents,” as Ilse Aichinger later wrote in her first and only novel, Die größere Hoffnung (The Greater Hope). Helga, the second born of the two twins, left Vienna in July 1939 on one of the last Kindertransports. Ilse, who did not want to leave her mother Berta behind, remained in the increasingly dangerous homeland. During the first stopover of the Kindertransport, Helga wrote a postcard to the family: “We are sitting here in the waiting room in Cologne after a 17-hour train journey and waiting for the other transport, which now, after we’ve been sitting here for at least 1½ hours, has to come in about 1 hour. Herta and I have already looked at Cologne Cathedral. It’s very beautiful.” Churches, and especially St. Stephen’s Cathedral, were of particular importance to the Aichinger family at this time. Again and again these appeared as code words in family correspondence. They refer to shared experiences, such as the “Rosary Mass” at St. Stephen’s Cathedral on October 7, 1938. At this service, Cardinal Theodor Innitzer spoke out against National Socialism in his sermon, prompting a spontaneous demonstration against the National Socialists, which was dissolved by the Gestapo. As a consequence, the Hitler Youth stormed the archbishop’s palace on the following day. An aid center for “non-Aryan Catholics,” one of the places where Ilse Aichinger found support during the war, had been established there. Both the “Donnerstagskinder” (“Thursday’s Children”) – a youth group led by Father Born and subordinate to the Archbishopric Help Agency – and the “Seegasse,” a street in Vienna-Alsergrund where the Swedish Israel Mission was based, can be found in encrypted form in their works, as well as in their letters.

Originally founded with the aim of converting Jews to Protestantism, the Swedish Israel Mission provided aid for the starving population during World War I and in the interwar period. From 1933 on they helped Jews to flee the “German Reich,” and from 1938 on to escape from former Austria. After the first Kindertransports left for Great Britain in December of that same year, they also sent around one hundred unaccompanied minors to Sweden. In 1941, the Swedish Israel Mission was closed by the National Socialists and the staff returned to Sweden. Ilse Aichinger experienced this as a cowardly betrayal. It became more and more dangerous for her and her mother in Vienna. Ilse – who was considered a “Mischling ersten Grades” (“a mixed-breed of the first degree”) – managed to protect her mother until the end of the war. However, she could not prevent the deportation of her grandmother Gisela and Gisela’s two children, Erna and Felix Kremer, on May 6, 1942. None of them survived.

In the meantime, Helga was trying to find her way in England. One anchor was her aunt, Klara Kremer, who had lived in Great Britain since the beginning of the year and had already helped arrange the Kindertransport. She also found stability in the Austrian communist youth group Young Austria, where she met her future husband Walter Singer. During the war, the two married and had a child, but divorced after the war. Presumably through Young Austria and the superordinate Free Austrian Movement, Helga made friends with Veza and Elias Canetti, Erich Fried, Anna Mahler and Hilde Spiel.

In the meantime, Helga was trying to find her way in England. One anchor was her aunt, Klara Kremer, who had lived in Great Britain since the beginning of the year and had already helped arrange the Kindertransport. She also found stability in the Austrian communist youth group Young Austria, where she met her future husband Walter Singer. During the war, the two married and had a child, but divorced after the war. Presumably through Young Austria and the superordinate Free Austrian Movement, Helga made friends with Veza and Elias Canetti, Erich Fried, Anna Mahler and Hilde Spiel.

© Privatbesitz Ruth Rix

Neither Ilse and Berta nor Helga could share sufficient information about the course of their now separated lives. With the outbreak of war, even the possibility of correspondence by letter was destroyed. All that remained was the writing of Red Cross letters, the content of which was limited to 25 words and visible to all. While the birth of Helga’s daughter was mentioned, the deportation of grandmother, aunt and uncle could only be made clear by omitting their names.

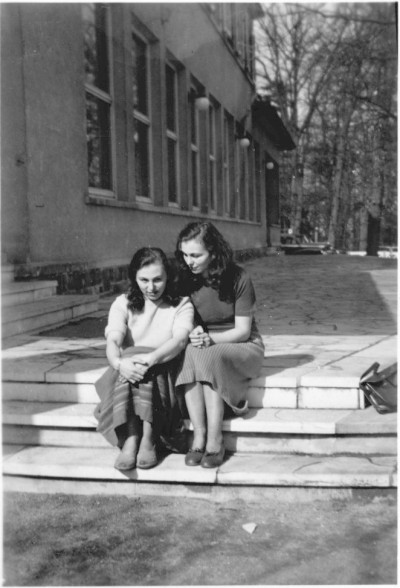

The twin sisters were prevented from seeing each other for more than eight years. It was not until 1948 that the surviving family members met for the first time in England. While Ilse already had some successes as a writer, Helga did not decide to become artistically active until the 1960s. She drew, worked with printing techniques and wrote poetry – however in English. She published her work under the name Helga Michie, since she had briefly been married to Donald Michie in 1958. Both twins repeatedly dealt with the topic of separation.

The twin sisters were prevented from seeing each other for more than eight years. It was not until 1948 that the surviving family members met for the first time in England. While Ilse already had some successes as a writer, Helga did not decide to become artistically active until the 1960s. She drew, worked with printing techniques and wrote poetry – however in English. She published her work under the name Helga Michie, since she had briefly been married to Donald Michie in 1958. Both twins repeatedly dealt with the topic of separation.

© Privatbesitz Ruth Rix

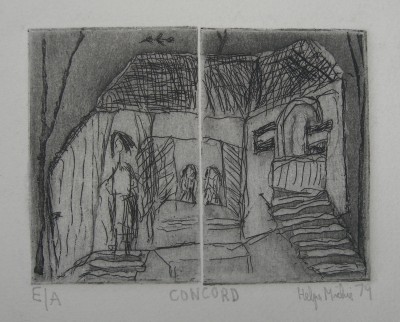

This becomes very clear, for example, in Helga Michie’s etching Concord, in which two small figures stand opposite each other in an almost mirrored fashion. While one is alone, the other has another larger figure at its side. Is it the mother who was protected by Ilse or the aunt who stood by Helga in England? If the two striped rectangles are interpreted as Austrian flags, then it is Ilse who is standing alone. This is similar to the fictional setting of The Greater Hope, in which the main character Ellen has to survive on her own, particularly after her sole caregiver, her grandmother, poisoned herself for fear of deportation. The title quote of this blog post comes from this novel: For Ellen, the passage of time is a deadly matter, because the further the war years progress, the more dangerous her situation as a persecuted child becomes, because she is a [one of the] “child [children] with the wrong grandparents, child [children] with neither a passport nor a visa, child [children] for whom nobody could vouch now.”

These children are the children of the Kindertransport and the children who stayed behind and often did not survive. Those who were able to flee in time are now themselves at the age of grandparents. For them, tomorrow is today and today is yesterday. But there should never have been children with wrong grandparents and without a passport. Because there are no wrong grandparents, and there must be no children without a passport, not today and not tomorrow.

As of November 10, 2021, you can see the story of the Aichinger twins and many others in our exhibition on Kindertransports at Museum Judenplatz: Youth without a homeland. Kindertransports from Vienna.

Works consulted:

Aichinger, Ilse. Die größere Hoffnung. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 1991.

Brogi, Susanna. “Kommunikative Überlebensstrategien im Exil. Der Briefwechsel von Helga Michie und Ilse Aichinger.” Häntzschel, Hiltrud, Sylvia Asmus, Germaine Goetzinger, Inge Hansen-Schaberg (eds.). Auf unsicherem Terrain. Briefeschreiben im Exil. Munich: edition text + kritik, 2013.

Ivanovic, Christine (ed.). I Am Beginning to Want What I Am. Helga Michie. Werke/Works 1968–1985. Vienna: Schlebrügge, 2018.

Ivanovic, Christine. “Aus der Geschichte der Trennungen. Die Zwillinge Ilse und Helga Aichinger.” Apostolo, Sabine (ed.). Jugend ohne Heimat. Kindertransporte aus Wien. Vienna: Jewish Museum Vienna, 2021.

Pammer, Thomas. “Die Arche Noah ist auf dem Kanal vorbeigefahren.” Geschichte der Schwedischen Israelmission in Wien. Vienna: Mandelbaum, 2017.

As of November 10, 2021, you can see the story of the Aichinger twins and many others in our exhibition on Kindertransports at Museum Judenplatz: Youth without a homeland. Kindertransports from Vienna.

Works consulted:

Aichinger, Ilse. Die größere Hoffnung. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 1991.

Brogi, Susanna. “Kommunikative Überlebensstrategien im Exil. Der Briefwechsel von Helga Michie und Ilse Aichinger.” Häntzschel, Hiltrud, Sylvia Asmus, Germaine Goetzinger, Inge Hansen-Schaberg (eds.). Auf unsicherem Terrain. Briefeschreiben im Exil. Munich: edition text + kritik, 2013.

Ivanovic, Christine (ed.). I Am Beginning to Want What I Am. Helga Michie. Werke/Works 1968–1985. Vienna: Schlebrügge, 2018.

Ivanovic, Christine. “Aus der Geschichte der Trennungen. Die Zwillinge Ilse und Helga Aichinger.” Apostolo, Sabine (ed.). Jugend ohne Heimat. Kindertransporte aus Wien. Vienna: Jewish Museum Vienna, 2021.

Pammer, Thomas. “Die Arche Noah ist auf dem Kanal vorbeigefahren.” Geschichte der Schwedischen Israelmission in Wien. Vienna: Mandelbaum, 2017.