1. Notturno for Strings and Harp [1896]; Performers: Daniel Hope, Zürcher Kammerorchester, Jane Berthe – 31,173,010 plays

2. Verklärte Nacht, Op. 4: I. Grave [1909]; Performers: Daniel Barenboim, Chicago Symphony Orchestra – 1,489,946 plays

3. Verklärte Nacht, Op. 4: IV. Adagio [1899]; Performers: Daniel Barenboim, Chicago Symphony Orchestra – 370,427 plays

4. 4 Pieces from 6 kleine Klavierstücke [1911]; Performers: Hans Abrahamsen, BIT20 Ensemble, Ilan Volkov – 360,843 plays

5. Verklärte Nacht, Op. 4 (Version for String Orchestra): V. Adagio (Bar 370) [1899]; Performers: Danish National Orchestra – 9,402 plays

In the overall ranking of classical music composers, Schoenberg stands well behind Mozart, Beethoven, and Mahler. Perhaps the reason for this may be his reputation as an experimental artist. His avantgarde works come across as atonal to an ear used to traditional harmonies.

His Spotify biography presents him as a rebel of the Viennese music scene: “Arnold Schoenberg remains one of the most controversial figures in the history of music. From the final years of the 19th century to the period following World War II, Schoenberg produced music of great stylistic diversity, inspiring fanatical devotion from students, admiration from peers like Mahler, Strauss, and Busoni, riotous anger from conservative Viennese audiences, and unmitigated hatred from his many detractors.” Through his multifaceted talents as a composer, theorist, writer, teacher, painter, and inventor, Schoenberg gained much attention already at an early age. While he had a considerable following of avid admirers, Schoenberg also encountered much resistance from his critics as his music provoked heated controversies within audiences.

“I write what I feel in my heart – and what ultimately ends up on paper

has effectively run through every fiber of my being.” (Arnold Schoenberg, 1937)

has effectively run through every fiber of my being.” (Arnold Schoenberg, 1937)

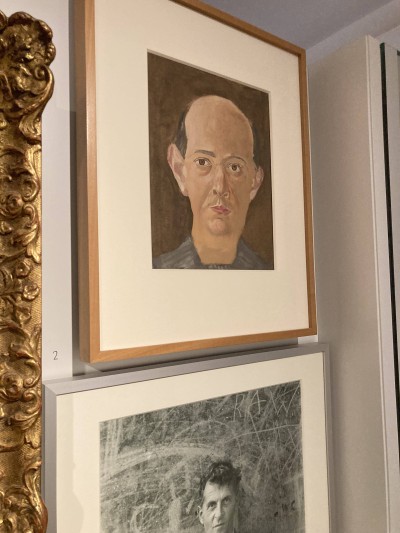

The Man behind the Music

150 years ago on September 13, 1874, Arnold Schoenberg was born in Vienna as the second oldest of four children to Samuel and Pauline Schoenberg. The Jewish family lived near the Augarten. Without much formal training, Schoenberg taught himself how to play the violin and began to compose music at just eight years old. He moved in the local artistic, literary, and music circles. Through which, he became acquainted with Karl Kraus, Alexander von Zemlinsky, Egon Schiele, and Oskar Kokoschka. These friendships shaped Schoenberg’s career and influenced the development of his music compositions. Stays in major European cities such as Berlin, Barcelona, Paris, and Amsterdam served as his inspiration as well.

150 years ago on September 13, 1874, Arnold Schoenberg was born in Vienna as the second oldest of four children to Samuel and Pauline Schoenberg. The Jewish family lived near the Augarten. Without much formal training, Schoenberg taught himself how to play the violin and began to compose music at just eight years old. He moved in the local artistic, literary, and music circles. Through which, he became acquainted with Karl Kraus, Alexander von Zemlinsky, Egon Schiele, and Oskar Kokoschka. These friendships shaped Schoenberg’s career and influenced the development of his music compositions. Stays in major European cities such as Berlin, Barcelona, Paris, and Amsterdam served as his inspiration as well.