You also had contact with the Austrian historian Albert Lichtblau, who had made scans of the postcards. In a conversation with him, you said that you were very lucky. To have survived the Theresienstadt camp, to have avoided three transports, to have made it to school and university after the war. You became an internal medicine doctor and ran a private practice for a long time. You concluded your thoughts on survival as follows: “I was also in the World Trade Center on September 10, 2001 and flew to Vienna that evening. So I’m curious to see what’s in store for me.”

Your donation to the Jewish Museum also includes a photo showing two women and two men; you could be seen on the very left. At least that’s what it says in the museum inventory. A journal book of the medical staff of a collection camp in Vienna is also part of the donation. The background is still unclear. You had found this book among your possessions. It may have come from the inheritance of your father, Dr. Paul Pollak, who was a police doctor. It contains entries and records from a hospital ward from January 1942 to February 1943. Collection camps were located on Kleine Sperlgasse, Castellezgasse, Miesbachgasse, and Malzgasse in Vienna’s second district.

As part of our cooperation with erinnern.at, we invited you to the museum for an event for teachers; that must have been before 2008. It focused on the stories and memories of contemporary witnesses and how or whether they can be applied in history lessons. We met beforehand at Café Teitelbaum, the name of the Jewish Museum’s café at the time, where we drank coffee and you asked for sticky tape. When I came back with it, there was a yellow piece of fabric next to your coffee cup. It was your Star of David badge that you had kept. I don’t know if you wanted to provoke those present with it. Perhaps you just wanted to see if anyone would ask you about it? Nothing happened. There was no reaction to the fabric attached to the left side of your jacket. After the event and on the way to the cloakroom, the star attached with sticky tape came off the jacket and fell to the floor. I noticed this and picked it up. You took the Jewish badge from my hand and said laconically: “It doesn’t hold up either.” I keep thinking about this scene and I wish I had asked more back then, earlier, when you were alive. Or had written a letter.

In the permanent exhibition Our City!, which opened in 2013, there is an area on the second floor where visitors can listen to seven contemporary witnesses via the free multimedia guide. They talk about life after survival. You are one of the narrators. In the immediate vicinity there is a display case in which a photo and an excerpt from Kurt Mezei’s diary can be seen.

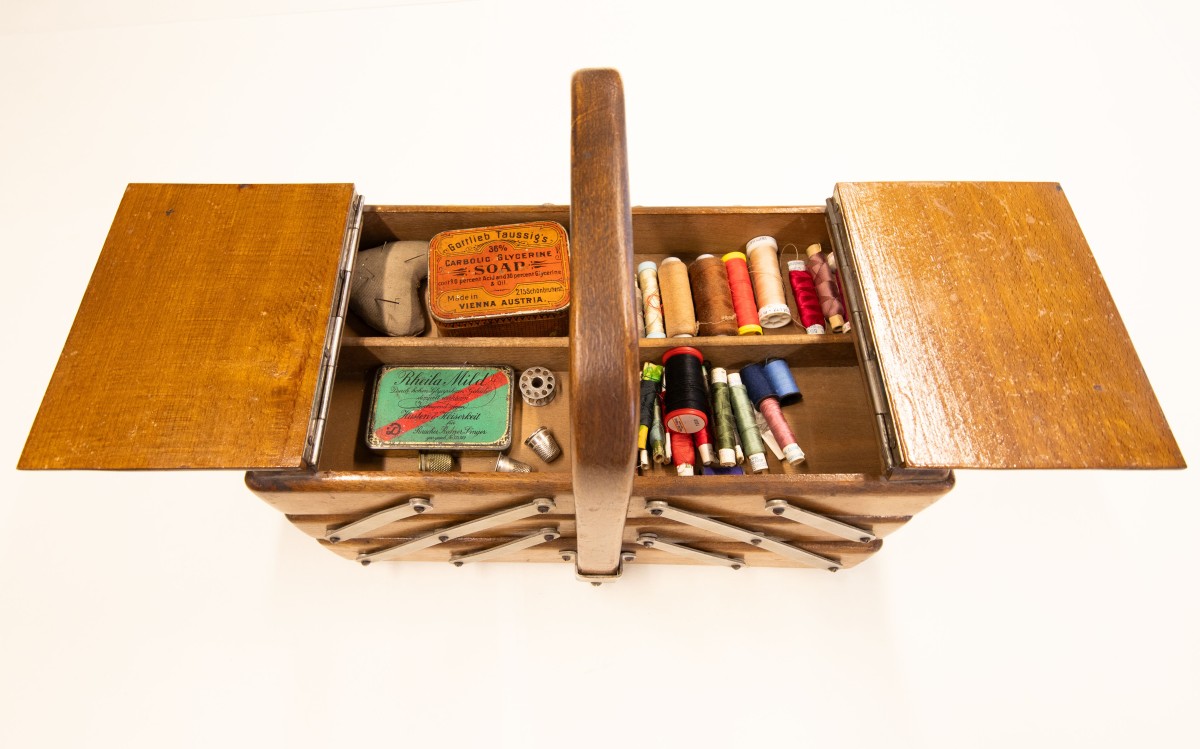

You are also part of the current temporary exhibition The Third Generation: the Holocaust in Family Memory. The parents of your husband Hans Busztin received their deportation notice in September 1942. Pepi Feldner, a doctor and bachelor friend, offered to hide the two sons. The parents were unsure whether hiding or fleeing would be more dangerous and separated the two children. Your future husband Hans, called Hansi back then, was the sole member of his family to survive in an apartment on Vienna’s Neubaugasse. The sewing box, along with a sewing cushion, had already been in this apartment, which is now a doctor’s office, in the 1940s. As a testimony to your husband’s survival, it is currently on display on the first floor of the museum. Your granddaughter, Anna Goldenberg, memorialized him and his rescuer in her novel Versteckte Jahre: Der Mann, der meinen Großvater rettete (Hidden Years. The Man Who Saved My Grandfather). His surname has become part of your family name.

23. October 2024

Latest News

Obituary Dr. Helga Feldner-Busztin (1929 – 2024)

by Hannah Landsmann

Dear Dr. Feldner-Busztin, Dear Helga,

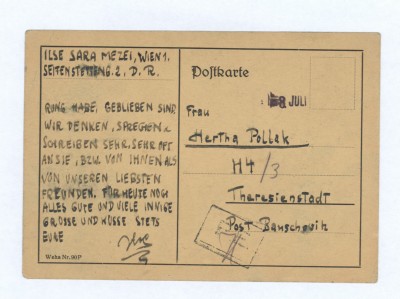

Since I now know that it can help the living to write letters to the deceased, the obituary for you will now take this form. We did not really know each other, but since you are represented several times in the Jewish Museum Vienna, this seems a viable way to me. In October 2008 you donated 55 postcards to the Jewish Museum Vienna, which had been written by Margarethe Mezei and her children Kurt and Ilse to you and your mother, Hertha Pollak. Your mother met Margarethe Mezei at a Viennese post office, and the two women realized that their husbands were imprisoned at the same camp in Italy. The 200 men were deported from there to Auschwitz and all but two were murdered. One of the survivors was your father, Paul Pollak, who was a doctor. You were a little younger than the two Mezei children, Kurt and Ilse, and became friends with them. In a conversation on the occasion of the donation of the cards to the museum, you said that you had tried out your cooking skills on the Mezeis; you served potato soup.

Since I now know that it can help the living to write letters to the deceased, the obituary for you will now take this form. We did not really know each other, but since you are represented several times in the Jewish Museum Vienna, this seems a viable way to me. In October 2008 you donated 55 postcards to the Jewish Museum Vienna, which had been written by Margarethe Mezei and her children Kurt and Ilse to you and your mother, Hertha Pollak. Your mother met Margarethe Mezei at a Viennese post office, and the two women realized that their husbands were imprisoned at the same camp in Italy. The 200 men were deported from there to Auschwitz and all but two were murdered. One of the survivors was your father, Paul Pollak, who was a doctor. You were a little younger than the two Mezei children, Kurt and Ilse, and became friends with them. In a conversation on the occasion of the donation of the cards to the museum, you said that you had tried out your cooking skills on the Mezeis; you served potato soup.

© Jüdisches Museum Wien

© Jewish Museum VIenna

© Tobias de St. Julien